Many populations of wildlife are remote, inaccessible or difficult to monitor. The advent of sub-metre, Very-High-Resolution (VHR) satellite imagery may enable us study these animals in a much more efficient way.

Over the past decade, BAS scientists have led investigations using satellite technology to identify, count and monitor different species in Antarctica and elsewhere. We have tested the capability of new satellites, applied bespoke methods to different species and developed automated counting techniques using Artificial Intelligence. These innovative developments have led to breakthroughs in the understanding of distribution and population trends, and increased uptake of the new technology by many other institutions and academics.

The main groups of animals on which we have focussed are:

Penguins

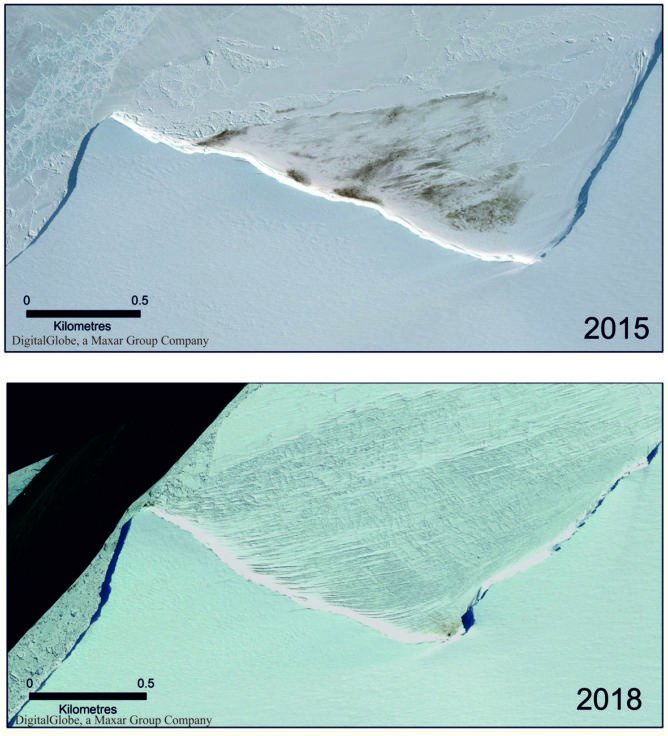

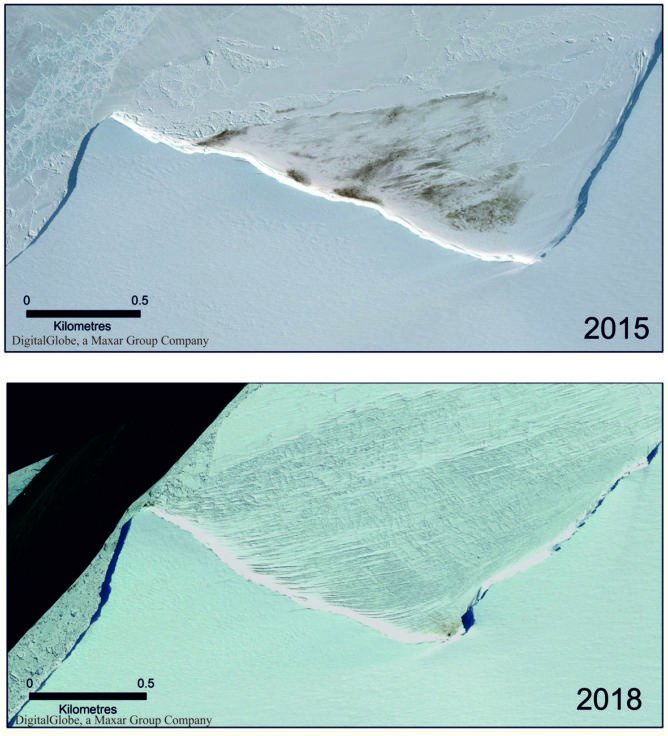

In the remote and inhospitable landscape around the Antarctic coastline, penguins can be challenging to monitor. For a decade, BAS has been locating, counting and studying colonies of emperor penguins to investigate the effects of climate change using vVHR satellite imagery. This work included the first global survey of a species from space (2012) and the discovery of many new breeding colonies. Since 2013, BAS has colaborated with WWF to monitor emperor colonies in a sector between 0° and 90°E. This includes sixteen breeding sites. Some of these have experienced dramatic changes in population sizes over time.

Emperor penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri) on sea ice at the Brunt ice shelf.

Satellite imagery showing the reduction in size of the Halley Bay colony in 2018 compared with 2015

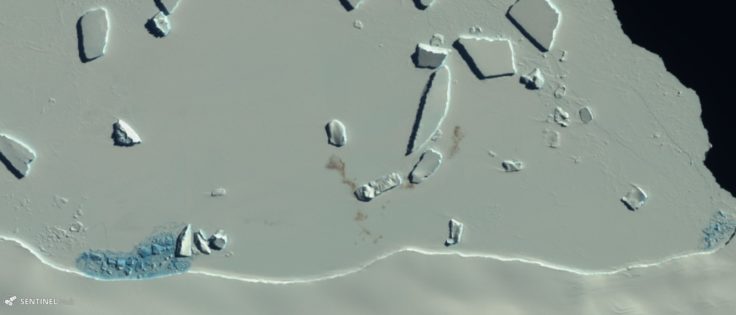

We have also used satellites to locate colonies and determine population trends of the smaller Pygoscelis penguins, such as chinstrap, Adélie and gentoo penguins. We used the unique spectral signature of guano to identify the breeding sites. Interestingly, the guano changes colour over the season, so as different species breed at different times we can tell the species by the colour of the guano at the time of the imagery.

Whales

Many whale species were brought to the verge of extinction in the age of commercial whaling, but since then some populations have started to recover. These species still face many threats, including ship strikes, pollution, entanglement and disease. Populations are difficult to assess by traditional means so BAS has led the study of baleen whales by satellite, a technology that could revolutionize how we monitor these animals.

A pod of southern right whales

We have tested the applicability of VHR satellites to identify and count several species (including humpback, sei, blue, southern right, grey and fin whales), analysed their reflectance (how easy they are to detect), developed automated counting techniques and examined how to convert satellite counts to abundance estimates. We have also investigated the use of satellites to identify and count stranded whales. Our research has led to the International Whaling Commission recommending a number of locations around the globe where use of the technology should be prioritized.

Seals

The sea ice that surrounds Antarctica is home to several species of seal that depend on it throughout their lives for resting, breeding, protection against predators and access to food. The vast size and dynamic nature of this frozen sea makes counting these seals incredibly challenging so that at present know little about how many there are and how their populations are coping with challenges such as climate change. We need to understand more about these seals as they are very important to the Antarctic Ecosystem. For example, crabeater seals are the most numerous seal in the world but at present we can only estimate their abundance as somewhere between 7 and 75 million individuals. Given they eat around 20kg of krill a day they have a large impact on the foodweb. Weddell seals, the second most abundant seal, like to live deep within the sea ice close to the Antarctic Continent making them very difficult and expensive to access and count.

Crabeater seals on an iceberg, taken on a boat trip from Rothera Research Station.

As part of the international Censusing Animal Populations from Space project, BAS is using VHR satellite images to study these ice seals. We are developing new methods to automatically detect and count seals, and classify the different environments they live in, including automated counting using machine learning and Artificial Intelligence combined with thermal imaging and spectral analysis.

Albatross

The great (Diomedea) albatrosses are the largest flying birds on Earth and they live on remote, inaccessible islands around the Southern Ocean. These charismatic birds face a number of threats including incidental mortality (bycatch) from longline fishing, invasive species, disease and habitat destruction.

BAS

Muchas poblaciones de vida silvestre son remotas, inaccesibles o difíciles de monitorear. La llegada de imágenes satelitales de muy alta resolución (VHR) submétricas puede permitirnos estudiar estos animales de una manera mucho más eficiente.

Durante la última década, los científicos de BAS han dirigido investigaciones utilizando tecnología satelital para identificar, contar y monitorear diferentes especies en la Antártida y en otros lugares. Hemos probado la capacidad de nuevos satélites, aplicado métodos personalizados a diferentes especies y desarrollado técnicas de conteo automatizadas utilizando Inteligencia Artificial. Estos desarrollos innovadores han dado lugar a avances en la comprensión de las tendencias de distribución y población, y una mayor adopción de la nueva tecnología por muchas otras instituciones y académicos.

Los principales grupos de animales en los que nos hemos centrado son:

Pingüinos

En el paisaje remoto e inhóspito alrededor de la costa antártica, los pingüinos pueden ser difíciles de monitorear. Durante una década, BAS ha estado localizando, contando y estudiando colonias de pingüinos emperador para investigar los efectos del cambio climático utilizando imágenes satelitales vVHR. Este trabajo incluyó el primer estudio global de una especie desde el espacio (2012) y el descubrimiento de muchas nuevas colonias reproductoras. Desde 2013, BAS colabora con WWF para monitorear las colonias emperadores en un sector entre 0 ° y 90 ° E. Esto incluye dieciséis criaderos. Algunos de estos han experimentado cambios dramáticos en el tamaño de la población a lo largo del tiempo.

También hemos utilizado satélites para localizar colonias y determinar las tendencias de la población de los pingüinos Pygoscelis más pequeños, como los pingüinos barbijo, Adelia y papúa. Usamos la firma espectral única del guano para identificar los sitios de reproducción. Curiosamente, el guano cambia de color a lo largo de la temporada, por lo que a medida que las diferentes especies se reproducen en diferentes momentos, podemos distinguir la especie por el color del guano en el momento de las imágenes.

Ballenas

Muchas especies de ballenas estuvieron al borde de la extinción en la era de la caza comercial de ballenas, pero desde entonces algunas poblaciones han comenzado a recuperarse. Estas especies aún enfrentan muchas amenazas, como colisiones con barcos, contaminación, enredos y enfermedades. Las poblaciones son difíciles de evaluar por medios tradicionales, por lo que BAS ha liderado el estudio de las ballenas barbadas por satélite, una tecnología que podría revolucionar la forma en que monitoreamos a estos animales.

Hemos probado la aplicabilidad de los satélites VHR para identificar y contar varias especies (incluidas las ballenas jorobadas, sei, azules, ballenas jorobadas, sei, azules, ballenas jorobadas, grises y de aleta), analizamos su reflectancia (qué tan fáciles de detectar), desarrollamos técnicas de conteo automatizado y examinamos cómo para convertir los recuentos de satélites en estimaciones de abundancia. También hemos investigado el uso de satélites para identificar y contar ballenas varadas. Nuestra investigación ha llevado a la Comisión Ballenera Internacional a recomendar varios lugares en todo el mundo donde se debe priorizar el uso de la tecnología.

focas

El hielo marino que rodea la Antártida es el hogar de varias especies de focas que dependen de él a lo largo de su vida para descansar, reproducirse, protegerse de los depredadores y acceder a los alimentos. El gran tamaño y la naturaleza dinámica de este mar helado hace que contar estas focas sea increíblemente desafiante, por lo que en la actualidad se sabe poco sobre cuántos hay y cómo sus poblaciones están lidiando con desafíos como el cambio climático. Necesitamos entender más sobre estas focas, ya que son muy importantes para el ecosistema antártico. Por ejemplo, las focas cangrejeras son las focas más numerosas del mundo, pero en la actualidad solo podemos estimar su abundancia entre 7 y 75 millones de individuos. Dado que comen alrededor de 20 kg de krill al día, tienen un gran impacto en la red alimentaria. A las focas de Weddell, la segunda foca más abundante, les gusta vivir en las profundidades del hielo marino cerca del continente antártico, lo que las hace muy difíciles y caras de acceder y contar.

Como parte del proyecto internacional Censusing Animal Populations from Space, BAS está utilizando imágenes de satélite VHR para estudiar estas focas de hielo. Estamos desarrollando nuevos métodos para detectar y contar sellos automáticamente, y clasificar los diferentes entornos en los que viven, incluido el conteo automatizado mediante aprendizaje automático e inteligencia artificial combinados con imágenes térmicas y análisis espectral.

Albatros

Los grandes albatros (Diomedea) son las aves voladoras más grandes de la Tierra y viven en islas remotas e inaccesibles alrededor del Océano Austral. Estas carismáticas aves enfrentan una serie de amenazas que incluyen la mortalidad incidental (captura incidental) de la pesca con palangre, especies invasoras, enfermedades y destrucción del hábitat.

Todas las grandes especies de albatros están amenazadas de extinción (https://www.iucn.org/), por lo que el seguimiento de sus poblaciones es fundamental. El estudio de sus lugares de reproducción remotos es difícil, por lo que estamos desarrollando métodos para contar y censar albatros automáticamente utilizando imágenes de satélite VHR. En 2014, realizamos el primer censo de una población completa por satélite, cuando contamos todas las colonias de albatros reales del norte en una sola temporada de reproducción.

:quality(85)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/PQ6CNZDSXFHJTKH4GUGH5T7QFI.jpg)

:quality(85)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/IQ2RNF4MN5FW5MIM77KG5BLLNA.jpg)

:quality(85)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/MJHFCJ6DMVHG7IMYMDZ6QGYALU.jpg)

:quality(85)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/DYMRP5S4P5A77OYVDTHDOBKKOI.jpg)

.jpeg)